So far I’ve tried to devote most of my posts to travel stories, with an occasional commentary on my favorite topics: the environment, energy, international politics and culture. However I recently had an idea that I’m dying to share with you, even though it’s only marginally related to my current travel adventures.

I want to talk to you about trash. And pollution. And how we can turn these things into valuable resources.

Last year I saw a video about what happens to electronic waste from the United States and other western countries. It shows how most of it is exported to places like Africa, India and China, and how one city in China is overrun with electronic waste pilling up everywhere. It gets sorted through and “recycled” by Chinese workers, who suffer from mercury poisoning and breath in toxic fumes from burning plastic. I saw some of this pollution first hand last summer, and it is not pretty. You can see some pictures of China’s worst waste and pollution disasters here (warning: some of these photos are quite disturbing, so don’t look at them right before eating dinner).

|

| E-waste dump in China. Image published by Time, 2009 |

If you are like me, looking at those pictures probably makes you at least a little queasy, and probably also makes you feel pretty pessimistic about the human race’s chances of survival if we keep doing things like this. From mountains of car tires, to millions of tons of food scraps, to electronic waste, to greenhouse gas emissions, our civilization is producing and dumping unimaginably large amounts of waste into the water, earth and atmosphere every day.

Ok, many of you already know this is happening. Some of you even have some ideas on how to solve it. But did you know there is an emerging school of thought that says that in fact we can recycle, reuse, and reduce our waste down to zero? When I was in elementary school, my 3rd grade teacher, Tom McKibben (brother of the climate activist Bill McKibben), asked me to draw an invention. So I drew what I called an “everything recycling machine.” You simply put all your trash into one end of the machine, and it would magically appear on the other side as something useful, like food or energy or water. Of course as I grew more mature, I realized that this was impossible… or was it?

Enter William McDonough, famous architect and author of Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. I saw him speak at the World Future Energy Summit nearly three years ago, but his words have stuck with me every since: “If our design is for destruction, then we are doing a pretty good job. If not, then we need a new kind of design.” His idea is that everything from your house to your car to the soles of your shoes can be designed in a way that it can be reused in the future, or when it gets discarded, it will be able to seamlessly integrate back into nature without any harmful side effects. Here’s another interesting article on how companies can design their products and services to be fundamentally sustainable by thinking about the materials going into them.

|

| Fully recyclable shoe based on the Cradle to Cradle method. |

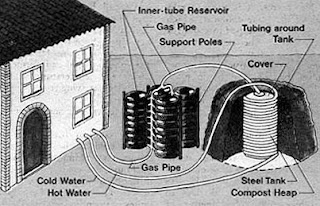

So here’s my idea. After successfully starting a compost pile at the Tufts European Center this summer (thanks to George Ellmore’s expert and enthusiastic advice), I started thinking about compost. Compost can be made from many things, but especially from what in fact accounts for almost 50% of our trash: food and paper waste. What’s more, as that compost is breaking down, it’s producing more than just fertilizer for your organic garden: it’s also releasing heat – enough heat to boil water – as well as methane gas, and water. Harnessing these resources can be achieved simply with a closed storage container for your compost, with tubes to siphon off the methane into one tank, and heat water in another tank. So what was once considered trash – food scraps, paper, other organic materials – could now be used to heat and power your house, as well as fertilize and water your garden! That sounds pretty close to an “everything recycling machine” to me. The saddest part is that a Frenchman named Jean Pain came up with this idea back in the 1980s, and its only now being given serious attention by cities like Boston as a way of using waste to solve our waste and energy problems. I think there might be a potential business in this idea.

|

| Jean Pain's compost to energy method. Image published by Reader's Digest, 1981 |

So I started thinking about where something like this would make sense. The first place that comes to mind is Dragon Spring Temple, the only temple in Beijing where there are still monks practicing Buddhism. My friend Bonnie, founder of an organization called Green Living, introduced me to the temple last summer. The temple is a beautiful and tranquil place, with an organic garden situated inside the walls. The only problem is that the inhabitants just set up a small coal power station to provide the temple with electricity. Since the temple houses nearly a hundred people in a nearby dorm, where they probably produce a lot of food scraps, an energy and organic fertilizer generating compost pile would make a perfect pilot project to replace the coal furnace.

This would be a great thing to implement on a large scale in China, because it addresses many of China’s environmental problems all at once: the need for waste disposal, clean energy and potable water (which can be extracted from the compost or added to fields with the fertilizer). But it would also make a lot of sense in my hometown of Freeport Maine, where the concentration of restaurants producing food waste (there are at least 30 in downtown alone), and organic farmers looking for non-industrial fertilizer right down the road, creates a perfect market. Going a step or two further, what if this technology were refined to the point where a small system could be retrofitted into every American home? In places like New England, where you are always raking leaves and hauling branches off your lawn, the products of these otherwise annoying chores could be put into a mini power plant to provide you with methane for producing electricity, heat for space heating and cooling, and fertilizer for your backyard garden! This could be the new Bloom Box, but unlike the Bloom Box it could probably be developed and scaled for much less money.

This might be my new project when I return to the US in a few years. For now though, I think being in China presents a great opportunity for a business like this. Now I just need to get my Chinese skills up to a business level…

Please comment and let me know what you think about this idea.